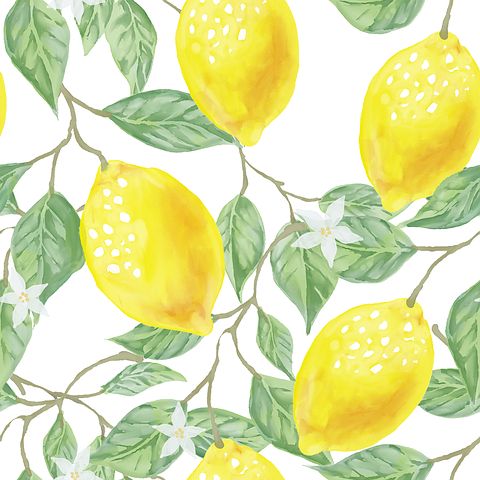

If you want to know just how attached the people of the coastal town of Menton are to their beloved lemon, look no further than the legend that credits its arrival on the French Riviera to Eve.

Expelled from the garden of Eden, the story goes, Eve plucked a lemon to take with her on the journey. Adam, fearing eternal condemnation, begged her to throw it away, which she obliged to do only in a spot of her choosing.

And thus, she found Menton, situated on the gleaming Bay of Garavan where the Alps rescind from the water just enough to create slopes with an east-west alignment – the perfect conditions for cultivating lemons.

While the legend itself is impossible to authenticate, the symbolism of the paradisiacal lemon is embedded in the folklore of this seaside town of about 30,000 inhabitants, where the bus line is called “Zeste” and a lemon motif seems the logical choice for many local businesses.

The town swells to nearly double its size during the Fête du Citron, an annual festival held in February celebrating the history and culture of citrus growing in the region, most notably of the Menton lemon, an officially recognised species that differs from Corsican, Spanish or Italian varieties in terms of its mild flavour and large, round shape with bumpy skin.

The allure of the festival lies in its floats and sculptures, each with more than three tonnes of lemons and oranges rubber-banded to a wire framework shaped to match the year’s theme. The Fête du Citron stands apart from other Carnival events in France in that municipal workers who spend most of the year maintaining city buildings are also the ones who prepare the floats and sculptures.

Titled Operas and Dances, the 2022 edition marked a triumphant return for the festival after it was cancelled midway through in 2020 due to the coronavirus pandemic. The Sunday parade was a jubilee of blaring marching bands, vibrant performers and six floats covered in lemons and oranges, some as tall as 10m, sculpted to represent the Samba, Can-can, Haka, Matachines, Salsa and Kathakali dance styles.

You may also be interested in:

• The French take on a trendy ‘superfood’

• The cake made with a 280-year-old water mill

• Is French cuisine forever changed?

From the floats, performers in costume worked alongside smiling city employees in neon-green safety vests to shower a seemingly infinite amount of confetti on the 15,000 spectators, whose outstretched arms made it clear they couldn’t get enough.

As the party raged on in the valley, the terraced hillsides overlooking the town harboured a harsher reality: Menton was once the leading lemon-growing region in all of Europe, but today, only about 15 producers remain. All the fruit for the Fête du Citron’s sculptures and floats must be imported from Spain.

“The annual production of Menton lemons is between 100 and 120 tonnes. In this period, we need between 150 and 180 tonnes of lemons and oranges. So, the production of Menton lemons wouldn’t be enough to create the whole of the Fête du Citron,” said Christophe Ghiena, the city’s director of technical services, who added that the remaining citrus is sold at discounted prices after the festival.

Aside from its Biblical legend, the documented story of the Menton lemon’s rise and fall began with its arrival from Spain in the 15th Century. The fruit quickly adapted to Menton’s temperate microclimate created by the unique combination of a protective mountain range and proximity to the ocean. By the end of the 18th Century, the region was estimated to produce one million lemons annually, said David Rousseau, director of Menton’s heritage department.

“In the 17th, 18th and 19th Centuries, the lemon was really the fortune of the city of Menton. Lemons were exported all the way to the United States, to Russia. It was a production of global scale,” he said.

It was a production of global scale

The Menton lemon’s decline began at the end of the French Revolution, when laws that had protected it against competition from other lemon-producing regions were lifted. The second blow came in the 19th Century, when the arrival of British winter tourists prompted the construction of hotels and villas on land used for citrus terraces. Finally, in the 1950s, an unusual cold snap spelled the Menton lemon’s demise.

“There was a big freeze in Menton and in France, which killed the remaining lemon trees,” Rousseau said. “It was in the 1980s that the lemon began to come back thanks to several producers who saw the lemon had potential and relaunched its production.”